Analysis from the 2024 BC Check-Up: Work report

Note to readers: At the time of writing in early October, employment data for September 2024 was not yet available. Prevailing trends outlined in this article, such as softer labour market conditions, continued into September, as the BC economy lost 18,000 workers and the unemployment rate rose 0.2 percentage points to 6.0% during the month.

CPABC recently released its third and final economic report of 2024, BC Check-Up: Work, which examines emerging trends in the BC labour market. Since last year’s edition, inflation has eased sufficiently to allow the Bank of Canada to begin lowering interest rates. While that’s welcome news for an economy that has been hampered by slow growth and softening labour market conditions, the question remains: Will we get the soft landing policy-makers have been hoping for, or are we in for a bumpy ride?

Table 1: Changes in Select Labour Market Indicators in BC, 2020 to 2024

| August 2023 | August 2024 | Change from August 2023 | Change from post-2020 best | |

|

Working age population |

4537.4 |

4689.9 |

3.4% |

n/a |

|

Employment |

2792.4 |

2839.0 |

1.7% |

n/a |

|

Unemployment rate |

5.3% |

5.8% |

0.5 ppts |

1.6 ppts |

|

Participation rate |

65.0% |

64.2% |

-0.8 ppts |

-2.0 ppts |

|

Employment rate |

61.5% |

60.5% |

-1.0 ppts |

-1.8 ppts |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-01.

Employment stalled while population growth accelerated

As noted in last year’s BC Check-Up: Work cover story,1 the BC labour market cooled between 2022 and 2023, easing from the incredibly tight conditions that characterized the post-lockdown era of the COVID-19 pandemic to those of a more balanced labour market. By August 2023, headline indicators, such as the unemployment and job vacancy rates, had returned to pre-pandemic levels, marking a short period of familiarity in very unfamiliar times. And although the economy did face several challenges—including elevated interest rates aimed at taming persistently high inflation, slow economic growth amid a surging population, and falling labour productivity—the labour market showed resilience.

Over the past year, the pace of inflation continued to slow, allowing the Bank of Canada to begin cutting interest rates—welcome news for Canadian labour markets, which had cooled off. In line with national trends, the BC labour market showed further signs of softening as well. As of August 2024, total employment in BC was 2.84 million, up 46,600 (+1.7%) from the year before. Notably, however, total employment fell between April and August, as younger British Columbians faced a challenging summer job market (see next section). This marked the first time that employment fell over a three-month period since the early months of the pandemic.2

As was the case in 2023, heightened levels of immigration helped bolster the province’s lacklustre employment numbers in 2024; however, this trend masked the underlying weakness of the labour market, as working-age population growth (+152,500 people or 3.4%) was double the rate of employment growth between August 2023 and August 2024 (see Table 1). As a result of this disparity, the employment rate dipped a full percentage point to 60.5%, the lowest rate BC has seen in more than three years. Additionally, the labour force participation rate (the proportion of the working-age population who are working or looking for work) was 64.2% in August 2024, down 0.8 percentage points from August 2023.

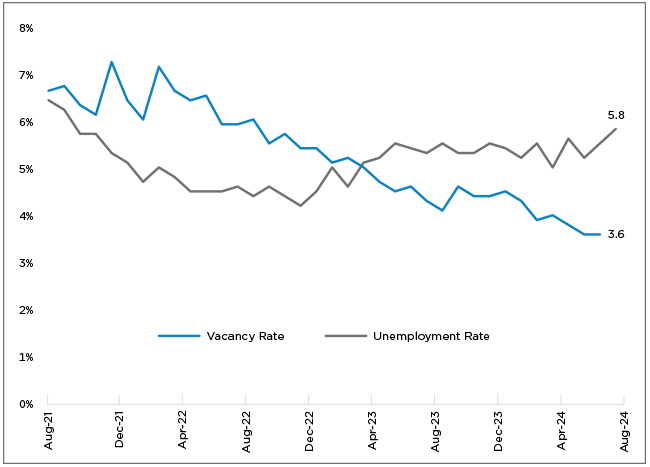

Weak employment growth was accompanied by an uptick in the unemployment rate. After staying in the 5.1% to 5.6% range for 16 consecutive months, the unemployment rate increased to 5.8% in August 2024. This is the highest rate recorded since September 2021, and it’s 0.9 percentage points above the 2017-2019 average. The upward trend in unemployment coincides with a gradual and persistent drop in the number of job vacancies over the last two years, as opportunities for job seekers have become scarcer. As of July 2024,3 the job vacancy rate (the number of unfilled positions as a proportion of total labour demand) was 3.6%, representing a seven-year low. This marks a retreat from the rate of 4.6% recorded in July 2023, which was above the 2017-2019 average of 4.2%.

Figure 1: Unemployment and Job Vacancy Rate, 2021-2024

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 14-10-0287-01 and 14-10-0432-01.

BC’s youth hit hard by job scarcity

The weakening of BC’s job market did not affect all demographics equally. BC youth (aged 15 to 24) bore the brunt of the impact, as 2024 produced a tough summer job market for students.4

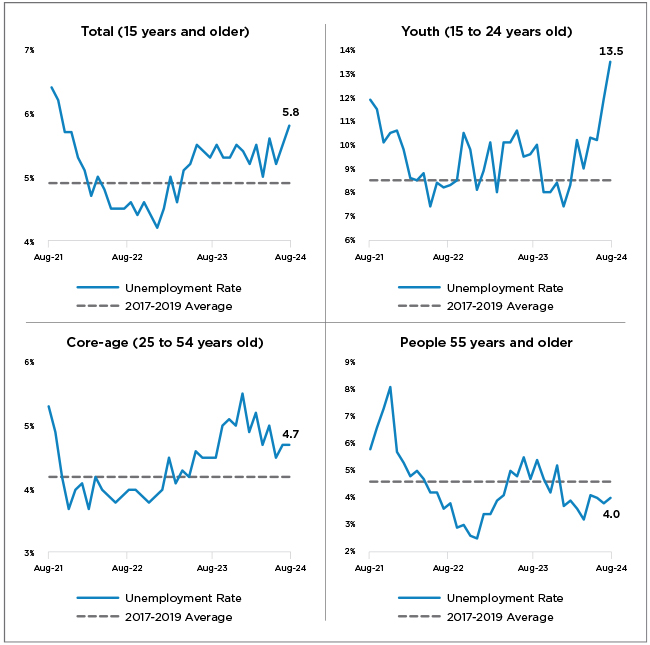

Figure 2: Unemployment Rates by Age Group, August 2021 to August 2024

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-01.

The unemployment rate for British Columbians aged 15 to 24 was 13.5% in August 2024, up 3.9 percentage points from the year before (see Figure 2). Conversely, the unemployment rate among residents in the other major age groups did not increase materially: The core-age working group (25 to 54 years old) had an unemployment rate of 4.7%, in line with the rate of 4.5% recorded in August 2023; and the cohort aged 55 and older had an unemployment rate of 4.0%, marking a 0.7 percentage point drop from the year before.

The numbers for BC’s young people become even more stark when considering those who said they wanted a job but did not look for one.5 As of August 2024, there were 17,800 British Columbian youth who wanted to work but were not in the labour force—nearly double the 9,000 recorded in August 2023. Taking these individuals into account, the adjusted unemployment rate for British Columbians aged 15 to 24 was 17.2%. Put simply, one in six BC youth who wanted to work were unable to find employment in August 2024, up from one in nine the previous summer.6

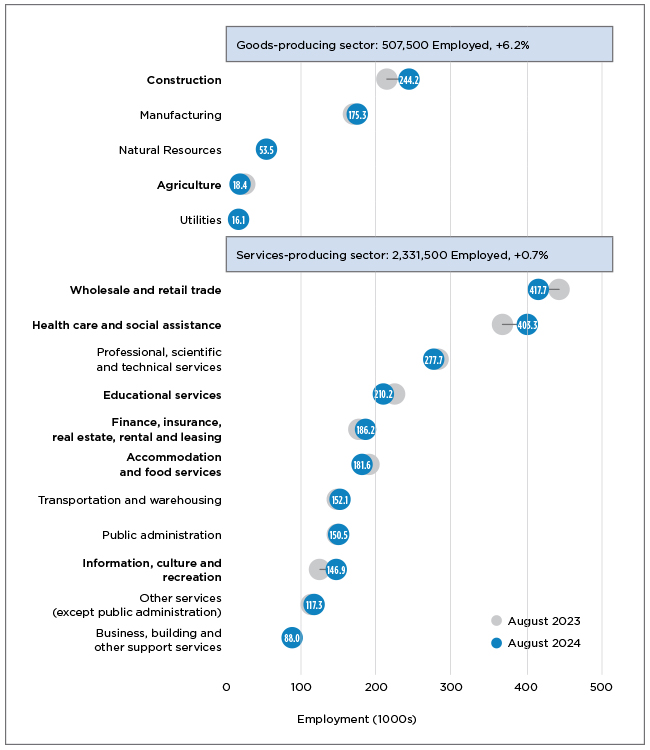

Rebound in goods sector drove employment growth

It’s not all bad news for BC’s employment numbers. The goods-producing sector added 29,600 workers (+6.2%) between August 2023 and August 2024, driven by a rebound in the construction industry, which added 31,700 workers (+14.9%) over that period. In fact, this increase in construction employment made up for the previous loss of 32,900 workers between August 2022 and August 2023. However, agriculture employment fell by 6,700 workers (-26.7%), and other industries in the sector experienced only marginal shifts.

Change in the services-producing sector was less significant. Employment in this sector edged higher by 16,900 workers (+0.7%), with gains in three industries and losses in three others (see Figure 3). Gains in health care and social assistance (+7.2%); information, culture and recreation (+15.1%); and finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (+7.4%) more than offset losses in wholesale and retail trade (-5.4%); educational services (-7.0%); and accommodation and food services (-6.2%).

While examining employment trends across industries provides valuable insights, looking at shifts by type of employment offers a more nuanced understanding of the drivers of employment growth. Public sector hiring buoyed the BC labour market between 2020 and 2023, while employment growth in the private sector remained comparatively muted.7 These trends continued over the past year, as the number of public sector and private sector employees rose by 2.9% and 1.9%, respectively, between August 2023 and August 2024. Over the same period, the number of British Columbians who were self-employed fell slightly, dropping by 1%.

Figure 3: Employment by Industry, August 2023 to August 2024

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0355-01. Subsectors have been sorted by total employment size as of August 2024. Industries with bolded labels indicate where the year-over-year change in employment was statistically significant.

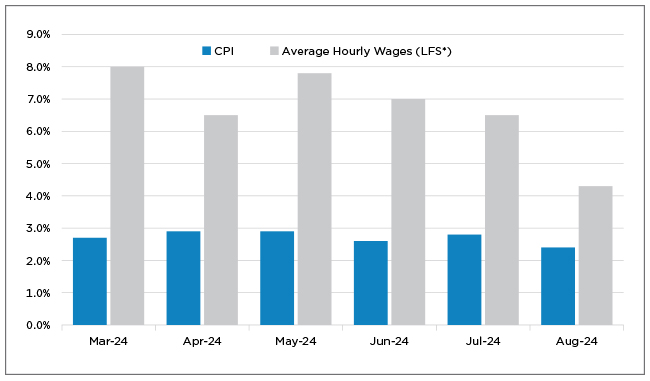

Wage growth continued to outpace inflation

Cumulative increases in average wages have exceeded price growth in BC since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and this trend continued in 2023-2024, with both inflationary pressures and average wage growth easing in recent months.

Average wages in British Columbia grew by 4.3% between August 2023 and August 2024, while consumer prices rose by only 2.4% (see Figure 4). This marked the 19th straight month that average wage growth outpaced inflation. Women experienced larger wage gains (+5.5%) than their male counterparts (+3.2%) during the year.

Figure 4: Year-over-Year Change in Consumer Price Index and Average Wages, March to August 2024

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 18-10-0004-01 and 14-10-0426-01. Data is not adjusted for seasonality. *Average hourly wage data is from the Labour Force Survey.

Where does that leave us?

All signs point to the fact that higher interest rates put downward pressure on the economy (as intended) over the past year, and BC’s labour market—much like the Canadian labour market—is showing some cracks.

Looking to the horizon, however, there is cause for cautious optimism. The consensus among forecasters8 is that economic growth will pick up again in 2025 amid further interest rate cuts, although it is unclear how much higher the unemployment rate will climb—or if we’re nearing the peak. Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem conveyed this uncertainty in the bank’s September interest rate announcement, saying: “We haven’t landed the economy yet. The runway’s in sight, but we have not landed it yet.”9

Jack Blackwell is CPABC’s economist. This article was originally published in the November/December 2024 issue of CPABC in Focus.

To access the full BC Check-Up: Work report, visit bccheckup.com.

Footnotes

1 Jack Blackwell, “Work in BC – BC Check-Up: Work Report Looks at Employment Trends Amid Persistent Inflation and Rising Interest Rates.” CPABC in Focus, November/December 2023 (16-22).

2 Employment fell by 27,900 people between April and July 2024. This was the first time since June 2020 that employment fell over a three-month period. On three occasions since then, a negative change was recorded, but it was not considered statistically significant.

3 The most recent month for which data is available at the time of this writing in early October.

4 Statistics Canada, “Labour Force Survey, August 2024,” The Daily, September 6, 2024 (www.150.statcan.gc.ca).

5 People who say they want a job but are not looking for one are considered to be “not in the labour force”—they are not counted as unemployed.

6 Adjusted unemployment rates are sourced from custom tabulations of Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey data and are not adjusted for seasonality.

7 Ken Peacock, “The Lack of Private Sector Job Creation in BC Should Be Setting Off Alarm Bells,” Economic Perspectives, bcbc.com, July 30, 2024.

8 Based on provincial forecasts from four of the largest Canadian banks (BMO, RBC, Scotiabank, and TD). Forecasts were made between September and October 2024.

9 Craig Lord, “The Bank of Canada Cut Rates Again. Here’s Why, and What’s Next,” Global News, September 4, 2024.